The King's English, but Does It Matter?

Most people in Europe, especially in the big cities, can speak English. We could have made our way through this entire trip in English. Wanting a fuller, more authentic experience, though, we studied some of the native tongues. Laura already knew a little French. I knew Spanish. And we studied some Italian. We were ready to build bridges through words.

Once we learned a little French in Paris, we got cocky. We could order breakfast with confidence: Bonjour! Un pain au chocolat. We felt positively Parisian. In retrospect, we probably should have tacked on a s’il vous plaît for politeness. And been a bit more humble.

Our first hint that we’d deluded ourselves came when we lunched beside the Musée d’Orsay. Artistic sidebar: it was at the Musée d’Orsay that we saw:

- Several paintings from Van Gogh

- Ball at the Moulin de la Galette by Renoir:

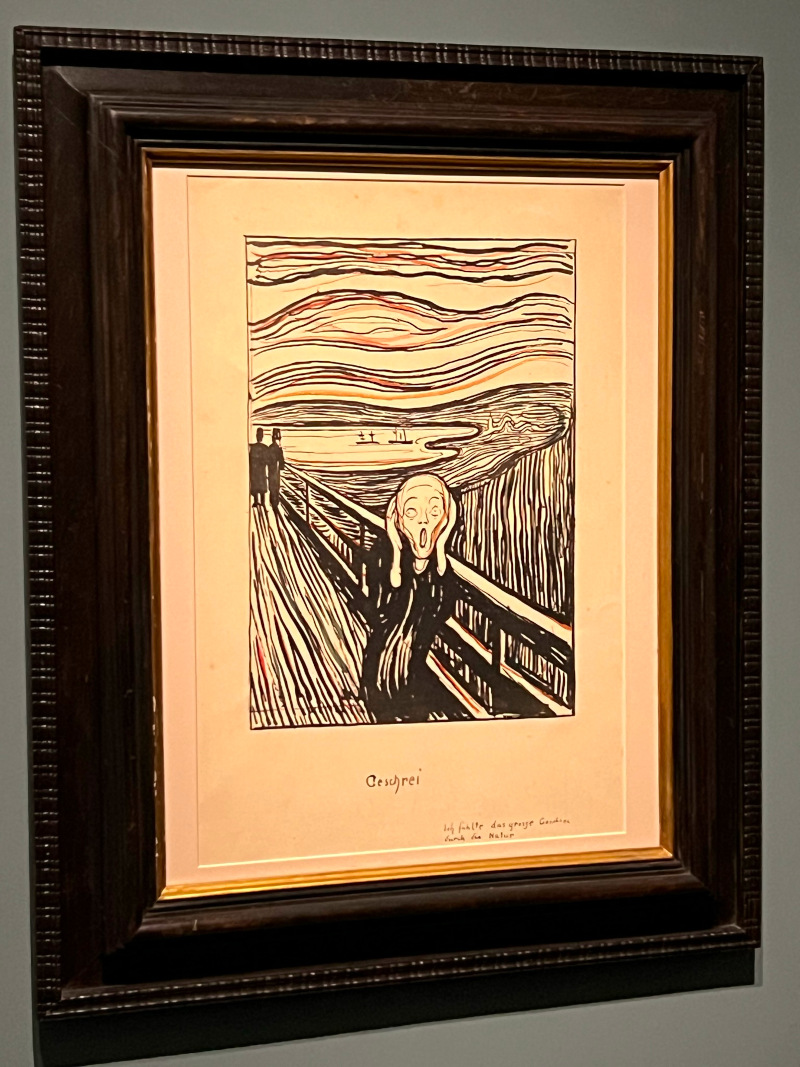

- An Edvard Munch exhibit that included a rendition of The Scream:

- Some amazing works by Kehinde Wiley:

- The Dancer by Degas:

So much great art! What a treat!

Anyway, lunch. Our waiter, an older gentleman, spoke no English. We exchanged French pleasantries, then pointed at menu items. No problem. Sherry got a little too comfortable, though, and ordered ratatouille. Seems pretty safe. After all, she’s watched the movie. Besides, what else on the menu could you confuse “ratatouille” with? So she ordered it by name. No pointing. Just the word: “Ratatouille.”

The waiter stared blankly.

She tried again: “Ratatouille.”

Now he looked perplexed, as if to say, “Are you ordering something? Calling me names? Singing that hip-hop music my grandkids keep trying to make me listen to?”

She tried one more time: “Ratatouille.”

He waved at the menu.

She picked up the menu and pointed to “Ratatouille” and repeated, “Ratatouille.”

His face lit up like the Eiffel Tower at night and said, “Ah, ratatouille!”

It sounded the same. OK, not exactly the same, but you couldn’t slide a five euro bill between the two pronunciations. Hers sounded like “radda-TOO-ee.” His “r” carried a bit of a cough, and his “t"s snapped like cap guns: “hrat-a-TOO-ee.” He might even have appended a tiny “ya” at the end. But again, virtually the same. Yet completely incomprehensible for a French-only speaker. We felt both humbled and outraged, like maybe he wasn’t trying.

The real snafu happened later, on the metro. We boarded the train and I grabbed a pole to keep my balance. It wasn’t enough. The train lurched, and I started to fall backwards. To avoid capsizing, I took a quick step back . . . squarely onto a woman’s foot. This was no casual toe-brush. This was a heel stomp, directly on the top of her foot. My brain raced through my French repertoire, frantic to make amends, and I blurted out the only word I could muster, “Merci!” My verbal blunder provided continued merriment for my travel companions through the remainder of the trip, but I doubt this woman felt amused. She may limp the rest of her life, and I’m thanking her for cushioning the blow for my errant foot. I imagine she went home that night and complained to her significant other, “You’ll never believe what happened to me on the metro today. I was sitting on the train, polite and composed. Not sprawling. Sitting. Taking only my fair share of space. And then this tête de merde tried to break my foot. My foot! Yes, of course he was American. And not small. Big. Heavy. You know how they get with their Big Macs and Big Gulps. And then, get this. He thanked me. ‘Thank you!’ he said. Like I’m some cushion for his oafishness! Do be a dear and get me some ice for this foot. And a bowl of hrat-a-TOO-ee-ya.”

I tried to make amends in Versailles when a guide asked the four us of what language we spoke. “Français? English? ¿Castellano?” Not wanting to be yet another monoglot American, I responded, “I speak English, y también yo hablo castellano.” Chuckling, he said, “I’m trying to determine which language to use to instruct you where to go. This is not a job interview.” Meekly, I said, “Merci.”

We did better in Italy. That’s where both Tina and I had focused our Babbel lessons. We knew things, like il mio ragazzo (“my boyfriend,” which realistically neither of us would ever say), and prendo un bicchiere di vino (“I’ll have a glass of wine,” which both of us said plenty). We even knew how to say, “Parlo un po d’italiano” (I speak a little Italian), which granted us near-citizenship, at least in our minds. We waltzed through Italy with scusi and grazie and buongiorno and buona sera, though a waiter in Florence chastised me when I said buona notte. You don’t say “good night” until you’re going to sleep, apparently, no matter the hour. You stick with buona sera (“good evening”) while you plan to stay awake.

Not that we didn’t have close calls. In a restaurant in Rome, I asked the whereabouts of the bathroom: “Scusi. Dov’è il bagno?” A funny thing about asking a question in recognizable Italian is that people tend to respond in Italian. Not even my boyfriend could help me understand the response. Lucky for me, I heard “scale” somewhere in the stream of gibberish. That sounded enough like “escalator” to lead me to the nearby stairs, and I found the bathroom near the foot of these stairs. Crisis averted.

Another tense moment happened in Rome when Sherry and I returned to our room to get our dirty clothes for a laundry run. Our rooms didn’t have numbers, but instead carried the names of colors. In a delightful coincidence, we had Florida Gator colors:

Our room:

Laura and Tina’s room:

When we got to our Orange room, the door was ajar and the maid was inside, cleaning. We walked in, and she looked at us, startled and dismayed. I hastily explained, “This is our room.” She shook her head. “English?” I asked. She shook her head. And then I froze. I couldn’t remember “our” (nostra), let alone “room” (stanza). So I did what any intelligent American would do: I talked slower and louder. “THIIIIS IIIS OUUUR ROOOOOOM.” I felt like E.T.. She continued to shake her head. I thought about ordering a glass of wine, or asking her about her boyfriend, but then settled on picking up my dirty clothes bag. This was a bad move. She put up her hands and took a step toward me. This woman was half my size and at least my age. She was ready to brawl to defend a stranger’s pile of dirty boxer briefs. This woman deserves a raise.

Before she could throw a punch, though, I remembered that I had the key to the room, with the “Orange” fob, in my murse. Sherry simultaneously remembered that she had Google Translate on her phone. I pulled the key. Sherry flashed “Questa è la nostra stanza” on her screen. And friendly relations resumed. We dropped our hands, laughed a little, and Sherry and I left with the clothes. And a resolve to pay more attention to Babbel.

One thing we learned in Italy: No is a complete sentence. One morning at breakfast, Laura ordered a combo platter and asked, “Can I substitute the croissant for toast?” It seemed a reasonable request. The menu listed both items, so we knew the restaurant had them. It’s the kind of request that American restaurants invariably accommodate, though sometimes with an additional charge. Our Italian waiter’s response, though, was simply, “No.” No explanation, no justification, no apology, not even a pained expression to soften the rejection. “No.” No substitution, no deviation, no discussion. We could learn things from the Italians.

The order of the cities we visited on this trip was:

- Paris (France)

- Rome (Italy)

- Venice (Italy)

- Florence (Italy)

- Genoa (Italy)

- Marseilles (France)

- Barcelona (Spain)

We bumped along fine until #6: the return to France. We’d done French in Paris. Then we’d transitioned to Italian for four cities. Now we were back to French in Marseilles. We couldn’t do it. Even a simple “Good morning” eluded us. Was it bonjour? Buongiornio? Il mio ragazzo? The simplest phrases melted like cotton candy from our brains. We were babbling infants. It was too much change, too quickly. Marseilles did have a couple lighthearted language moments, though. One morning, Sherry and I walked past a homeless woman jonesing for a smoke. She was perched on a windowsill beside a bakery. When she saw us, she started puffing an imaginary Virginia Slim while hollering, “Seegaret? Seegaret?” We stared forward as we walked past, pretending we heard nothing. On the return trip, she was still there, and tried the same tactics. On a dare from my wife, I responded in Russian: “Pozhaluysta. Pozhaluysta.”

Later, two elementary-age girls approached us with a bag of candy. I think they were trying to sell us the candy, but the European pickpocket horror stories made me clutch my murse. Sherry responded in a language only she knows: “Scanna kolanna bindolan panfred.” The girls jumped back, puzzled, and Sherry had another go: “Andurello gopanko undini.” Giggling, they ran away. I relaxed my hold on my murse. We foiled them.

Barcelona gave us a more solid lingual footing. I lived in Chile for two years, from 1988-1990, during the waning days of Pinochet’s dictatorship. Some of my Spanish has faded in the intervening 30+ years, but I’ve retained enough to remain reasonably fluent. I fretted a little about the so-called “Spanish Lisp”, wondering if I needed to adopt it in Spain. I did a little research, paid a little attention, and learned:

- It’s mildly offensive to call it a lisp, because it isn’t a speech defect. It’s a purposeful pattern of speech.

- The oft-repeated tale that Spain adopted this speech pattern to avoid humiliating a lisping king is false, as I always suspected but had never confirmed.

- Not everyone in Spain uses this speech pattern. I heard plenty of both “GRAW-see-us” and “GRAW-thee-us.”

I spoke mostly Spanish while in Spain, and understood most of what I heard. People understood me. Spain felt more immersive, more like home, to me. I conversed with shopkeepers, taxi drivers, waiters, and people on the street in their language. I ordered food in Spanish, spoke to a pharmacist about acetaminophen in Spanish, discussed best places to live in and near Barcelona in Spanish. Perhaps the most rewarding conversation, though, was with a waiter in an outdoor restaurant a block from our hotel. We were ordering paella, and somehow he mentioned that he was from Chile. “¿Chile?” I exploded. “¡Soy más Chileno que los porotos!” This means, “I’m more Chilean than beans!” and is the standard way to declare one’s Chilean origins. Even though it’s apparently inaccurate. He laughed, I howled, and we bonded as hermanos chilenos. It was a fun exclamation point, both upside down and right side up, for our trip.

Now that we’ve all decided to move to Barcelona some day, we’re all learning Spanish. Could we get by with English in Spain? Probably. Mostly. But we’ll have more fun, meet more people, and bond more closely with the people and country if we speak Spanish. And if I inadvertently stomp on a woman’s foot on the Barcelona metro, I’ll smile and say, “Grathias.”