A Roo Awakening

No country owns an animal like Australia owns the kangaroo. OK, China and the panda play in the same league. But China and its one-trick panda can’t match Australia’s array of exclusives: koalas, platypuses, echidnas, wallabies, wombats, emus, Tasmanian devils, and more. Australia’s geographic isolation has created a mix of species that techies would call “proprietary” and scientists call a high level of endemic fauna. You and I just say, “OMG that’s a lot of cool animals!” You can’t call a trip to Australia complete until you put eyes on kangaroos, koalas, and other animals you won’t see anywhere else. We spent portions of three different days in zoos, and got an eyeful of everything but echidnas. The lone, bashful echidna we had the chance to see, a resident of the Melbourne Zoo, stayed hidden. Something else we didn’t see at the zoo: Jhett. By the time we went to the zoo in our second week in Australia, he’d left for a week-long work placement assignment for school. We missed having him with us!

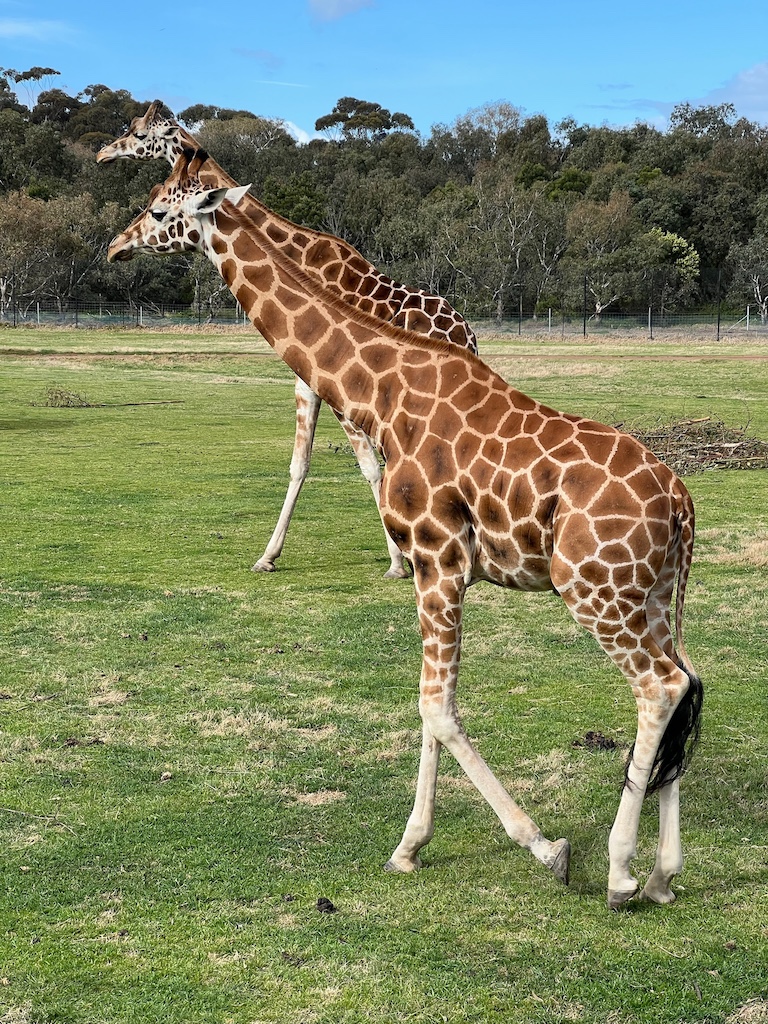

Australian zoos, of course, don’t restrict their populations to endemic species. The zoos we visited sported a smattering of animals from other continents, including zoo mainstays like elephants, lions, giraffes, and monkeys. We also saw animals you don’t necessarily see in U.S. zoos, like a red panda and a cassowary. We had to chuckle, though, when one of our tour guides tried to hype a herd of American bison. Yes, they’re majestic and shaggy and powerful. We gaped at them in Yellowstone the last time we were there. We cheered Derrick White throughout the NBA playoffs and the Paris Olympics. But we’d traveled 10,000 miles to see the symbol of the American West? I mean, we see plenty of bison in the U.S. We eat bison. We watch ads with talking bison every time we watch a football game:

Once we got past the irony of traveling halfway across the world to see American bison, though, we enjoyed the view of the bearded herd. And we silently gave thanks that the tour didn’t include an alligator exhibit. We see plenty of alligators in the ponds by our house:

Our first zoo: Werribee Open Range Zoo. As its name indicates, this zoo forsakes the smaller, species-specific cages seen in most zoos. Instead, it has vast ranges ringed by Jurassic Park-like fences and gates. Compatible species share ranges. You ride a tram through most of the park, your driver doubling as tour guide. For smaller ranges, you ditch the tram and go on foot. The animals go anywhere they want within the enclosure, while you’re on your honor to stay on the paths. Ropes indicate the human boundaries. The animals ignore the ropes, ducking under them as they please.

From the tram, we saw giraffes, ostriches, and zebras sharing a savanna-like expanse. Australians pronounce the name of those stripey horses “ZEH-bras,” not “ZEE-bras.” I toyed with asking the driver why they didn’t call them “ZED-bras,” but didn’t want to have to explain the joke. The giraffes followed the tram, feigning indifference, as if they just happened to be going the same way we were. As we puttered along, the giraffes kept pace like gawky basketball centers. It felt like being stalked by Victor Wembanyama and Chet Holmgren. The ostriches and zebras stayed distant, impervious to the tram and us goggling viewers. Here’s a good pic of a couple giraffes:

The murderous hippos had their own range. Who wants to live with a hippo? Or more accurately, die inside one? These hippos sprawled, catatonic, like Tide fans on their Barcaloungers. Perhaps they were digesting the last batch of foolish humans who sneaked into their pen. Only the occasional ear twitch proved they were alive, not statues. Here they are beside their pond:

Lest anyone mistake their lethargy for harmlessness, the zoo posted “Beware Hippos” signs. Graphic, gory, and a bit disturbing, the signs seemed to be the work of preteen boys. Here’s one:

Yes, this wannabe cave art depicts a hippo eating a human head-first. Drops of blood stream at an angle, down and back, as if the hippo is charging forward as he chomps. The sign hangs for all to see, from graybeard to toddler, with no parental warning. I guess Australians are a hardy lot. Or perhaps the painter was the owner’s nephew. Either way, I suspect they don’t have much trouble with folks sneaking into the hippo enclosure.

The grey kangaroos and the emus shared one of the walking areas. A path, lined with rope boundaries, cut through it. The kangaroos, wary of human visitors, stayed at the far end of the pen. We pined for binoculars and zoomed our iPhone cameras. Every now and then, a kangaroo would turn its head to check us out. Mostly, they ignored us. The emus, while also having no interest in human interaction, refused to be hemmed in. They stalked freely across the path, dashing away when some tourists (not me!) approached too close with their cameras.

Undoubtedly, the most curious animal I saw was an odd bird with blue and green feathers. No sign marked the name of the species, and no guide was around to ask. Smaller than an emu yet larger than a kookaburra, this bird had a large wingspan and kept asking me to buy her treats. I was able to snap a picture:

Our other two animal encounters took place at Melbourne Zoo on succeeding days. Sherry, Russ, and I went the first day, enticed by the Meerkat Experience. The second day, Russ slept in while Sherry and I returned for the Australian Wildlife Experience. I recommend both.

One thing we learned about Melbourne: mums take their small children to the zoo. Schools of all ages take field trips to the zoo. Children pour through the zoo’s turnstiles like New Yorkers emerging from Grand Central Station at rush hour. Awash with children of all ages, the zoo gave us a sort of zoo-within-a-zoo: wild animals viewing wild animals. They ran like rhinos, screeched like baboons, whined like mosquitos, and fought like chimpanzees. The tensest moments came in the butterfly exhibit, where the rules to “be quiet” and “don’t touch” went largely unheeded. We could see the effects of past student hordes — many butterflies had chunks missing from their wings, like this:

One butterfly found refuge atop Russ’s hat:

Sharing the zoo with so many children chattering like cockatoos made us realize that, though we enjoyed the moments when we were raising children, we lack the energy for steering that chaos anymore. If any of our children ever give us grandchildren, though, we’ll suck it up and take them to the zoo. Some traditions deserve to continue.

Melbourne Zoo, like Werribee Open Range Zoo, boasts a wide variety of animals. While we had the most interest in the Australian animals, we went to all the exhibits. Elephants, lions, giant tortoises — we saw them all. Just as when Russ was growing up and going on field trips to the zoo, I pulled my traditional gag:

Me: “When we get to the monkeys, make sure you don’t stand too close to the cage.”

Russ: “Why?”

Me: “The workers might think you’re an escaped monkey, and put you in the monkey cage.”

He now tolerates this running joke. Barely. I wish I’d known about his autism when he was young, though. I now have a sense of his confusion: how could I think that the zoo workers would mistake him for a monkey? And I appreciate why he seemed so earnest when trying to help me understand that no, no one would think he was a monkey. No one would incarcerate him in the monkey cage. Sometimes, I shake my head at what an infantile parent I was. Regardless, I continue to parent my adult children in the only infantile way I know how. They’ve aged out of my ability to influence them, anyway. I’ve probably done all the damage I can do. So I trot out the same lame jokes, and they play along. Barely.

Yes, Russ has learned patience. I have taught him patience. As we approached the zoo, for example, I lofted my favorite zoo joke: “I once went to a zoo that had only a dog.” Russ rolled his eyes and deadpanned, “It was a Shih Tzu.” Then he shook his head.

Side note: I got one genuine laugh from Russ on this trip. He was talking about Whole Foods, and I said, “I don’t understand how they have a store called ‘Whole Foods.’ I mean, once you get past donuts and Lifesavers, what else is there?” He laughed and said, “That’s actually funny. With most of your jokes, you try too hard, but that one was good.” He has ensured that I’ll keep trying.

When we got to the lemur cage, it appeared empty. When we gave up and moved on, though, we found them in another section of their enclosure. We tried to get them to sing “I Like to Move It,” but they just stared — perhaps out of respect for Erick Morillo:

The highlight of the first Melbourne Zoo visit: the Meerkat Experience. Meerkats are one of Russ’s favorite animals, a fact I didn’t know until that moment. When our appointment arrived, a young Australian zoo worker took us to the zoo’s erstwhile elephant shed, now pachyderm-free. Decades ago, elephants used to live in the shed and provide rides at parties. Melbourne Zoo has moved on from those days, transforming into a “conservation organisation committed to fighting wildlife extinction.” No more stuffing elephants into small sheds. They keep the shed to preserve history, and to provide a place for Meerkat Experiencers to create enrichment activities for meerkats.

We filed into the shed and took seats at picnic tables. Tins of Crayolas sat on the tables. While our guide talked about the history of the elephants and the shed, I tried to imagine what we would be drawing for meerkats. Did they prefer earth tones, pastels, primary colors, or neons? What would we draw? Whatever the drawing assignment, I resolved to produce the best drawing. As it turned out, though, the crayons were a red herring. They had nothing to do with us or the meerkats. Instead, our guide passed out chunks of rubber hose, each between 20 and 30 centimeters long. She also gave us some kind of food pellets — I think they were cat food? — and some excelsior. Under her direction, we stuffed the excelsior into the tubes. Then, we shoved a few pellets into each tube, hidden in the excelsior. We would give these to the meerkats, and they’d use their digging habits to pull the wood shavings from the hoses to get the pellets. As we dutifully stuffed hoses, I gazed longingly at the crayons.

We donned masks. Our guide told us to keep our voices low so we didn’t spook the meerkats. She also cautioned us about 47 times not to touch them. We entered the meerkat enclosure, sat on benches, and gawked. The meerkats milled before us. I tried to count how many times Sherry said, “Ohmigosh they’re so cute!” but I lost track. Russ kept giggling his giddy giggle that he gets when excited. Zoo workers gave the meerkats our hoses. They also gave them black plastic squares that had grids of pockmarks. Other volunteers had inserted kernels of corn into each divot. The meerkats, oblivious to our presence, went to work digging out corn kernels and food pellets. We sat like statues, hands clasped so we wouldn’t be tempted to pet them, breathing softly so they wouldn’t scatter. Here are some pictures:

After our time with the meerkats, we moved on to the lion cage. The viewing room for the lion enclosure offered a close-up of two male lions, pacing back and forth in unison. They continued their synchronized pacing the entire time we watched. Why did they pace? Stress? Boredom? Training for a new ABC/Disney crossover competition called “Dancing with the Scars”? As guests came and went, I watched to see whether the lions adjusted the limits of their path based on where people stood — perhaps they were stalking us as prey? No matter where the people were, however, the lions never altered their pivot points. Not even for small, defenseless children.

A web search turned up a gamut of opinions about lion pacing, from “It’s a sign of stress and shows why zoos are mankind’s worst invention” to “This is normal lion behavior.” This link seems fairly comprehensive, reasonable, and instructive: Why Do Lions Pace.

On to the platypus. The platypus house boasted a large aquarium with a restless platypus. Low lights simulated night-time so that the platypus, a nocturnal creature, would come out from hiding for the tourists. After all, if it stayed in hiding, guests would think it was actually an echidna. The platypus swam around its tank unpredictably and energetically. I’m not sure if it was searching for food, a mate, or that echidna. It swam too fast for my phone’s camera to get a good picture in the low light. A lot of the pictures I took show an empty tank — by the time I snapped, the camera fired, and the picture took, the platypus had moved outside the field of view. The ones that captured the platypus were blurry. This may be the best picture I got:

Sherry got a video of the platypus, though:

Next up: Tasmanian devils. My father, who used to live in Melbourne and has visited Tasmania, describes Tasmanian devils as “nasty creatures.” Wikipedia concurs. Among other things, all of which merit reading, the Wikipedia page says:

It [the Tasmanian devil] is characterised by its stocky and muscular build, black fur, pungent odour, extremely loud and disturbing screech, keen sense of smell, and ferocity when feeding.

The eight-year-old boy in me hankered to see the Tasmanian devils. Sadly, none of the Tasmanian devils we saw screeched or showed ferocity. Admittedly, we didn’t shove our noses right up to them, but we smelled no pungency. I expected dervishes of destruction, like those old videos of piranhas in the Amazon River devouring cows to the bones in seconds. What I saw looked more like moody, slightly irritated rodents, meandering about their enclosure. Sometimes, they just slouched on the ground like the hippos:

Here’s a shot of one on its feet:

Looney Tunes has a Tasmanian devil character named Taz. He looks like this:

Compare my pictures to the Taz picture. Taz has the big head, the fangs, and the surly personality correct. Everything else is wrong: the color, the body shape, the bipedal locomotion. This link explains why the cartoon character looks so different from the real animal. A quote from that page:

[Robert] McKinson (the creator) meant to base Taz off a real Tasmanian devil, but as he was looking for inspiration, the animator was only drawn to certain aspects of the animal.

Me? I think he first drew a faithful Tasmanian devil, saw that it looked like a dog-sized rat, and riffed until he arrived at Taz. And maybe the meerkats stole his black Crayola.

At the zoo gift shop, I bought a small, plastic Tasmanian devil in a ferocious pose. It now sits on my desk amid all my other tchotchkes. I’m not sure why I find these beasts so intriguing, but I have a theory: with my children grown and gone, I miss having cranky teenagers around. The Tasmanian devil is the perfect surrogate.

Buoyed by the success of the Meerkat Experience, Sherry decided we’d return to Melbourne Zoo the next day for the Australian Wildlife Experience. This adventure begins before the zoo opens, so we’d missed our chance that first day. Russ bowed out, saying that a 7:45am arrival was too early for him. Besides, he sees all these Australian animals in the bush on forays with Jhett. I dragged my feet as well, thinking of both the time and the price tag for yet another experience with animals we’d already seen, albeit from outside their enclosures. Before I could dissuade her, though, Sherry got online and booked tickets. At that point, it was all over but the hopping.

Our tour guide for this adventure was another young woman. Her name was Katy, or perhaps Kelly, and she was from the U.S., from a small town outside of Austin, Texas. She’d lived in Australia for six years, and had gotten her zoology degree from the University of Melbourne, where Jhett studies. What’s more, she has family in Florida, and has visited St. Augustine Wild Reserve, where we volunteer a couple times a month. Like the other guide, she was knowledgable about the animals and passionate about her work. What she lacked in the cool accent department, she made up for in zoological knowledge. We learned a lot from her — for instance, that the reason burrowing animals (e.g., Tasmanian devils) have big heads is so that, as long as they dig wide enough for their heads to fit, the rest of their bodies will fit, too.

The starring attraction for the Australian Wildlife Experience was, of course, the kangaroos. These were Kangaroo Island Kangaroos, a shorter and stockier subspecies of Western Grey Kangaroos. They evolved on an island — Kangaroo Island — secluded from natural predators. Consequently, they don’t know to fear humans, making them ideal for an immersive experience. The ones at the zoo shared an enclosure with emus and wallabies. Once again, we received instructions not to touch, be loud, or make sudden movements, and we entered the enclosure and sat on benches.

The wallabies did not evolve on Kangaroo Island. They have predators. They stay on their guards. While we sat on the benches, they kept their distance, hanging out on the edges of the enclosure. The emus wobbled between curiosity and caution, staying close enough for us to take pictures but far enough that I didn’t worry about them snatching out my eyeballs with their fearsome beaks. Mostly. The workers poured heaps of food into troughs that sat in front of the benches, mere feet from our feet. The kangaroos hopped right over and dug in, mostly ignoring us. Every now and then, they’d check us out. I noticed one looking at us:

“That looks familiar,” I thought. “Where have I seen that look before?” And then I remembered:

My lovely daughter Shiloh, from 12 years ago!

They loved the carrots, picking them up with their paws and nibbling on them like Southerners eating corn-on-the-cob. One kangaroo chewed on a mouthful of carrot, lazily holding the rest of the carrot in his paws. Another kangaroo stretched its neck over and bit off a hunk of the carrot the first kangaroo held. Just snatched a bite right from the other kangaroo’s paws. We braced ourselves for a squabble, anticipating a round of slap boxing and karate kicks. Instead, the first kangaroo glanced over at the carrot thief, metaphorically shrugged, and went back to eating. The keepers said such food sharing is typical. These are beasts accustomed to safe surroundings and plenty of food. Why would they scuffle over a carrot?

The workers dispensed the food in three layers, stratified by desirability. Carrots were at the top, along with other fruits and vegetables, as I recall. I don’t recall what the middle layer was. At the bottom, least desirable, were the pellets. These kangaroos ate dessert first, and then worked their way to the boring nutrition. As the top layers ran low, the kangaroos started checking to see if we had anything to offer. They quickly figured out we didn’t, but not before we took a picture:

The emus hovered around the edges, looking for opportunities to dart in and snag snacks. The keepers would shoo them away, but every now and then an emu would score. As the kangaroos drifted away, leaving the pellets for later, I caught a pic of a couple emus gobbling pellets:

The rest of the experience involved staying out of the cages, but we still had the same tour guide and enjoyed learning more about the Australian birds and animals. We learned what everyone with an Internet connection knows: quokkas look like they’re always smiling. They’re the happiest animals on earth. Humans? They love ’em. Love posing with them for selfies. Love the company. They brim with joy, always. Here’s an example picture I swiped from Reddit:

What we also learned, that not everyone knows, is that the “smile” is an anatomical quirk. It lies. They’re not smiling, and they’re not happy to see you. They’re timid, wild animals that fear humans in the same way rabbits, squirrels, or rats do. Tourists are stressing out all the quokkas. They swarm the quokkas’ home, Rottnest Island, invading their personal space to get these smiling selfies. Quokkas actually don’t enjoy this. Animals, in general, don’t appreciate TikTok challenges, believe it or not. In the zoo, we saw quokkas; they looked like this:

No smile. No pose. No thrill to appear in my picture. It’s not seeking clout or to socially influence. We should leave the quokkas and their fake smiles alone.

When we got to the echidna cage, we looked in all the places the guide thought likely. No luck. The echidna continued to hide. Two days, no echidna. We moved on.

We spent some time learning about wombats. Wombats burrow into the ground to create wombat warrens where they live, sleep, and hide from predators. When they emerge to poop or to find food, they wander. I tried to get a good picture, but they didn’t want to pose. Here’s a sample:

As cute as they are, though, you can see how simply they’re shaped. They’re like a furry smoked sausage with feet. Making a wombat stuffed animal, for example, would be a great candidate for your first ever sewing project. Want a clay wombat? Roll out a chubby clay snake, break it in half (because you made it too long for a wombat), and stick some clay nubbins on it for feet. Want a five-minute wombat? Grab a brown woolen sock, stuff it with cotton balls, and tie off the opening. Instant wombat.

One more word on wombats. The Internet has assured we all know a few biological facts:

- Mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell

- Otters hold hands while they sleep so they don’t drift apart

- Wombats poop cubes

“Aha!” I thought. “This is my chance to verify the doo-doo dice!” I scoped out a stack of scat, snapped a pic, and zoomed in. See for yourself:

Are they cubes? Well . . . kind of. They look like toddlers tried to make round balls from Play-Doh, but their undeveloped fine motor skills ensured that they squashed the sides a bit. Not balls, not cubes. Somewhere in between.

Our tour guide explained that the flattened sides hinder the poop from rolling back into the wombats’ burrows. This seems a strange evolutionary adaptation to avoid taking a few more steps to answer nature’s call. In fairness, I don’t want to walk a long way in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom, either. But I’m now more suspicious of the otter thing.

One other wombat weirdness, which our guide talked about, is that they have buns of steel. More accurately, their butts comprise “four fused plates surrounded by cartilage, fat, skin and fur.” They’re not fleshy; they’re hard. They use their hard backsides for defense — wombat combat consists of turning tail to their foes to block entrance to their burrows. Immature wombat children stir up trouble using this anatomical oddity, having conversations with their parents like this:

Parent wombat: “Willy Wombat, you’re in trouble! Quit leaving your poop cubes all over the burrow!”

Child wombat: “Why are you being such a hard-ass?” (Giggling)

Parent: “That’s enough! You’re getting punished!”

Child: “What are you going to do? Spank me?” (Giggling more)

Wombat teenagers are the opposite of human teenagers: hard-bottomed instead of hardheaded.

The last animal we saw was the koala, the other quintessential Australian animal:

In the pantheon of cute, cuddly animals, koalas cavorted near the top for decades. Their big, fluffy ears and diminutive size guaranteed people would swoon at pictures of them, snuggle koala-shaped stuffed animals, and long for the day they could squeeze a live one in their arms. Sadly, the Internet shattered the veneer of the koala image. Specifically, Reddit ruined koalas for the masses. If the koalas’ fall from grace is news to you, prepare yourself before clicking that link. Koala truth isn’t pretty. Still, we’d paid the money, and where else are you going to see a koala but in Australia? Russ said he’s seen plenty in the wild, but this was our koala viewing. And we enjoyed it. And ignored what Reddit told us. This koala was clean, awake, and cute. And it wasn’t training its offspring in eucalyptus consumption.

Our zoo visits rank near the top of the highlights from our trip. Mingling with meerkats and kickin’ it with kangaroos? How do you top that? If you ever travel to Australia, don’t miss the chance to see the animals found only there. Some parting thoughts:

- If you mentally corrected “platypuses” to “platypi” when reading the opening paragraph, you’re wrong.

- Until I see a Tasmanian devil actually acting out, I’ll remain skeptical of their ferocity. They may just need to hire a new Public Relations agency.

- Australia still owes me an echidna viewing.

Finally, here’s a shot of the three of us at Werribee Open Range Zoo, ready for our safari!